Articles and Papers

BOOK:

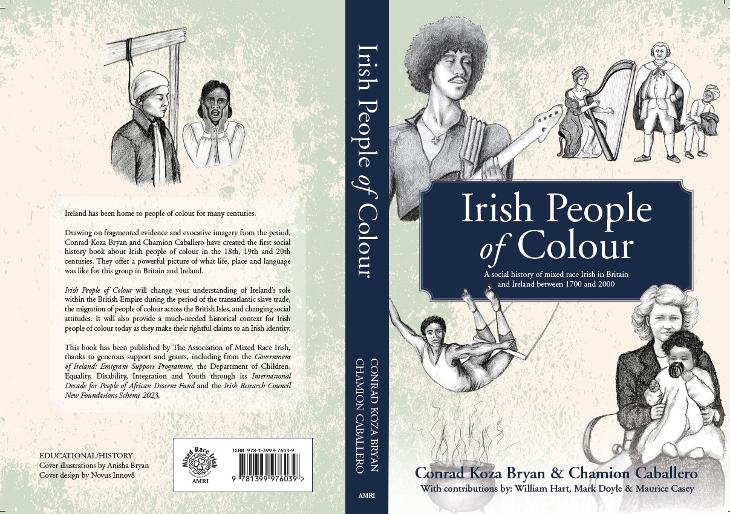

Irish People of Colour - A Social History of Mixed Race Irish in Britain and Ireland between 1700 and 2000.

by Conrad Koza Bryan and Chamion Caballero - with contributions by William Hart, Mark Doyle and Maurice Casey

May 2024

This is the first social history book to be published about Irish people of colour in Britain and Ireland. It will be published at the end on May.

Thanks to the generous grants received from the Irish Government's Emigrant Support Programme, the Irish Research Council New Foundation Scheme 2023, International Decade for People of African Descent Fund, and other donations the Association of Mixed Race Irish is able to publish this exclusive non-profit first edition to be donated to schools, colleges and public libraries across Britain and Ireland.

We are grateful to the authors and contributors for their tireless work and research, over many years, raising awareness about this minority community, a community which is part of the extended Irish nation and family, both in Ireland and in the diaspora. (Enquiries to info@mixedraceirish.ie)

This edition is not available for purchase is shops, as this edition is primarily for schools and public libraries and funded events, however, some workshops will be organised in Ireland during 2024 by Maynooth University, at which attendees will receive a free copy. We will announce these here in due course.

Conference paper:

The Pursuit of Justice in Ireland

16May 2023 - Conrad Bryan talks about Irish childcare institutions at a conference in Ghent University in Belgium about THE BELGIUM Métis (mixed race)

Exhibition: Telling the untold stories of mixed race Irish families in Britain

20 August 2020 Irish Times

by Conrad Bryan

Being Irish, mixed race and living abroad: it's complicated

1 December 2017 Irish Times Abroad

By Conrad Bryan

A State Apology

4 April 2021 - Belgium apologised to mixed race people in 2019

by Conrad Bryan

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

On this day two years ago, on 4 April 2019, the Belgium federal government gave a State Apology to mixed race people ( known as Métis) , for forced abductions from their African mothers in colonial Africa, forced adoptions, lost identities, targeted segregation and institutionalisation in Belgium.

Sounds familiar? This will resonate with mixed race people across Europe who find themselves caught up in the legacy of the decolonisation of the African states in mid-20th Century.

Each European state will have a different take on and history of African colonisation and decolonisation. Ireland, for example, though not generally considered a colonial power itself, was historically part of the British Empire. In the 1960s Ireland saw a significant influx of African students from decolonising African States to study subjects such as medicine, law and government administration.

Some of these African men had relationships with white Irish women and had mixed race children, many of whom were left in Irish state Institutions run by religious orders. In Belgium, a colonial power, abducted mixed race children from their colonies who were institutionalised by religious orders.

Under colonial rule, mixed couples were prohibited. They were subject to social stigma and sanctions. Métis children were seen as a problem, a dangerous element, even a threat to the colonial system.

The colonial authorities and the Belgian state at the time took measures to fight against miscegenation. These children were taken from their African mothers and generally educated by nuns in orphanages or boarding schools, far from whites and blacks.

Between 1959 and 1962, the Belgian state transported hundreds of these children to Belgium, usually without the permission of their African mothers. The children were either adopted by Belgian families or placed with foster families or institutions.

Ladies and gentlemen, the distribution of Métis children over the entire territory of Belgium was effected by separating siblings and led to losses of identity due to the various changes of first names, names and even dates of birth. Many are without birth certificates or identity papers.

Another factor has also made things worse for Métis children. In Belgian Africa, the Métis were considered as belonging to the category of higher degree of civilisation known as "evolved", because of their partly white origins and, if their father had recognised them, they were Belgian citizens.

However, a ministerial circular of September 24, 1960 addressed to the mayors recommended that, if the bond of filiation was not established, the child should be considered as African. To those for whom this link was not established, identity cards for foreigners were therefore granted.

Despite the fact that, later, the laws made it possible to recover this nationality within a certain period, due to a lack of information, few Métis made use of it and many of them had to go through the naturalisation procedure in order to '' acquire Belgian nationality. It was difficult and extremely painful for the Métis children to then rebuild their lives in Belgium.

The emotional abandonment experienced during childhood, uprooting, administrative difficulties as well as the need to assume a double identity without knowing one's origins have undoubtedly constituted a daily challenge and a real suffering.

The House last year approved a resolution condemning the targeted segregation of which the Métis were victims under the colonial administration of the Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Burundi until 1962 and after decolonisation, as well as the policy of forced kidnapping going hand in hand with the latter. The Catholic Church of Belgium also apologized to the victims concerned for the role it played in this regard.

During the hearings, the federal government undertook to take the results of your work into account. Several meetings were organised with several firms and administrations concerned, but also with representatives of the Belgian Métis Association.

A cooperation agreement has been concluded between the FPS External Relations and the Archives of the Kingdom, with a double objective: to allow the archives to be consulted by those concerned and that they can obtain information, on the one hand, and research scientists, on the other hand. This research is spread over four years. An initial financing of 50,000 euros has already been achieved. Métis files that were kept at the Africa Museum were transferred to the Kingdom Archives.

The Belgian Métis Association has drawn up a list of the difficulties that still arise. With regard to Belgian nationality, the persons concerned were invited to submit their individual request, supported by a relevant and complete file, to the FPS Justice. The latter will examine them within the framework of its powers.

With regard to civil status documents, the FPS Justice will propose as soon as possible a maximum of possible solutions within the limits of the existing legal framework. In addition, the Minister of Justice informed the College of Public Prosecutors of any difficulties that the persons concerned may have encountered regarding the individual proceedings in progress.

Ladies and gentlemen, by setting up a system of segregation targeted against mixed-race people and their families in Belgian colonial Africa, the Belgian state carried out acts contrary to respect for fundamental human rights. This is why, in the name of the federal government, I recognise the targeted segregation of which the Métis were victims under the colonial administration of the Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi until 1962 and following the decolonisation as well as the related forced kidnapping policy.

On behalf of the Belgian federal government, I apologise to the mixed-race people from Belgian colonisation and their families for the injustices and the pain they suffered. I also wish to express our compassion for the African mothers whose children have been torn away.

I hope that this solemn moment will be an additional step towards an awareness and a broad understanding of our national history. I of course also hope that this declaration will strengthen our determination to fight relentlessly against all forms of discrimination, racism or xenophobia.

Despite this tragic history, many mixed race people from colonisation have actively participated in the development of a more open and tolerant society, rich in its diversity. This opens up hope for the future that we will all be optimistic messengers for a respectful and solid alliance between Europe and Africa. “

The Belgium Catholic church also apologised for their role in these human rights violations.

While working through the Mother and Baby Homes Investigation recently in Ireland, I have had the pleasure to find time to meet with our sister organisation in Belgium called the Association Métis de Belgique, who are still seeking justice and reparations for the wrong that was done to them even two years after the State apology.

Today I would like to draw your attention to the apology made by the Belgium State in 2019. How children of African descent were treated in European states is an issue that needs to be looked at from human rights and racial justice perspective. It is often linked to the legacy of European colonisation, see the translation of the apology below:

On the 4 April 2019 in the Federal houses of Parliament, the President of the assembly spoke briefly before introducing the Prime Minister Charles Michel to give the apology.

The President of the assembly said:

“This is about a past that is still alive and well, but also about much more than that. This sensitive issue is symbolic, but above all human. For some, it is even a cause of trauma.

I would also like to welcome the presence in this hemicycle of several representatives of the MiXed2020 and Métis de Belgique / Metis van België Associations which bring together the Métis born in the territories under Belgian colonial domination.

For many years, the discrimination suffered by Métis from Belgian colonization in Africa was considered a taboo subject in Belgium and very often overlooked.

Yet there are thousands of Métis children who grew up without knowing their real family and who were placed in orphanages and foster families between 1959 and 1962, sometimes without birth certificates or nationality.

It all started in Flanders. Following actions by the ASBL Mater Matuta and the research of several historians, the Flemish Parliament unanimously adopted two resolutions in January and June 2015 which recognise the victims of forced adoptions. The Flemish Parliament even issued a public apology on November 24, 2015.

An important colloquium was organized in the Senate on April 25, 2017. This colloquium was an opportunity to address in particular the question of the arbitrary classification of Métis by the colonial administration as subjects of customary law and non-citizens of Belgian civil law and of learn about the study by Cegesoma (the Center for Studies and Documentation of War and Contemporary Societies) relating to the transfer of mixed-race children to Belgium at the end of the colonial period.

In June and July 2017, three other parliamentary assemblies, the Senate, the Parliament of the French Community, whose presence of the President in the gallery I welcome, as well as the French-speaking Brussels Parliament also adopted a resolution relating to this segregation.

Several colleagues therefore rightly felt that the House should follow suit. The Foreign Relations Committee therefore unanimously adopted a resolution on March 7, 2018 so that the House of Representatives also expresses itself on the subject and officially recognizes these facts.

It was also a question of ordering the government to take several actions allowing at least partial reparation for those who suffered in one way or another by the actions of the Belgian authorities in these circumstances. This resolution was then adopted by the Chamber during the plenary session of March 29, 2018…”

Prime Minister Charles Michel then gave the State Apology which is as follows:

“Discrimination against Métis resulting from Belgian colonisation in Africa has been suppressed for a long time.

On the eve of the wave of independence in Africa, several thousand Métis children were nevertheless living in Belgian Africa. In most cases, they were children of Belgian men who held a post in Africa and of Congolese, Rwandan or Burundian women.

© Copyright The Association of Mixed Race Irish